In 1932, in Cavendish University, J. D. Cockcroft and E. T. S. Walton bombarded lithium with protons from a particle accelerator. The protons caused the lithium atom to split. Many scientists realised that if they continued to split uranium and plutonium atoms, with the protons from one atom splitting another and the process repeating in a process called fission, they could make a new source of energy. However, with this power, the results could also be used for much more sinister means.

August, 1939. About a month before the outbreak of WW2, Albert Einstein, a highly accomplished scientist who discovered the theory of relativity (E=mc2) sent a letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt, then President of the United States, on a highly serious matter. Einstein believed that the Germans were working on a super weapon, a super weapon that would harness the power of Cockcroft and Walton’s work and make a fission bomb, that could wipe cities off the map. Despite being a pacifist, Einstein believed that such a weapon would be better in the hands of the Americans than the Germans. By October of 1942, two months before American entry into the conflict, the development of an atomic weapon was granted by FDR. A group of hundreds of scientists all were called upon by the US government to assist in the development of the technology.

One of the top scientists on the project, who led the scientific research and design of the bomb, was Dr J Robert Oppenheimer. He graduated in chemistry from Harvard and got a doctorate in physics from the University of Gottingen in Germany. He learned a lot about quantum physics, a field that was not that expanded in the US.

One of the most notable German physicians was Werner Heisenberg, who thought of the famous Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle. Many believed that Heisenberg was working on the German Nuclear bomb.

Back to Oppenheimer, he joined the faculty of the University of California, where he expanded the field of Quantum Physics in the United States. He even partially discovered a black hole in 1939. He was considered to be one of the greatest minds in Atomic Research, the kind of man that the US was after. Him, as well as many other notable scientists such as Richard Feynman, Edward Teller and Isidor Isaac Rabi, were gathered in Los Alamos, a remote part of the New Mexican Desert where a small town was built in order for the scientists to do their research.

The project, named the Manhattan Project, was worked on for months on end. The first contained chain reaction occurred in a secret lab under a Chicago University football stadium. The theory’s were now fact and the development of the bomb begun. During the time creating the bomb, Italy fell after an allied invasion and a small civil war. The Axis powers were on the ropes and the President, now Harry Truman after the death of FDR on April 12th of 1945, was confident that this bomb would be the final push to end the German War Machine. However, it ended a lot sooner than expected.

On the 21st of April 1945, the Soviet forces entered Berlin. Only 9 days later, Hitler fed cyanide to his wife, Eva Braun, and shot himself in his bunker in Berlin. 2 days later, Germany surrendered. 2 out of the 3 major Axis powers were out of the war as well as the bomb’s target. Truman began to reconsider the target. He had been bombing the Japanese for months on end and he believed that a mainland invasion of Japan would only cost more American lives. With the Soviets beginning to invade Japanese occupied Manchuria, he decided what to do.

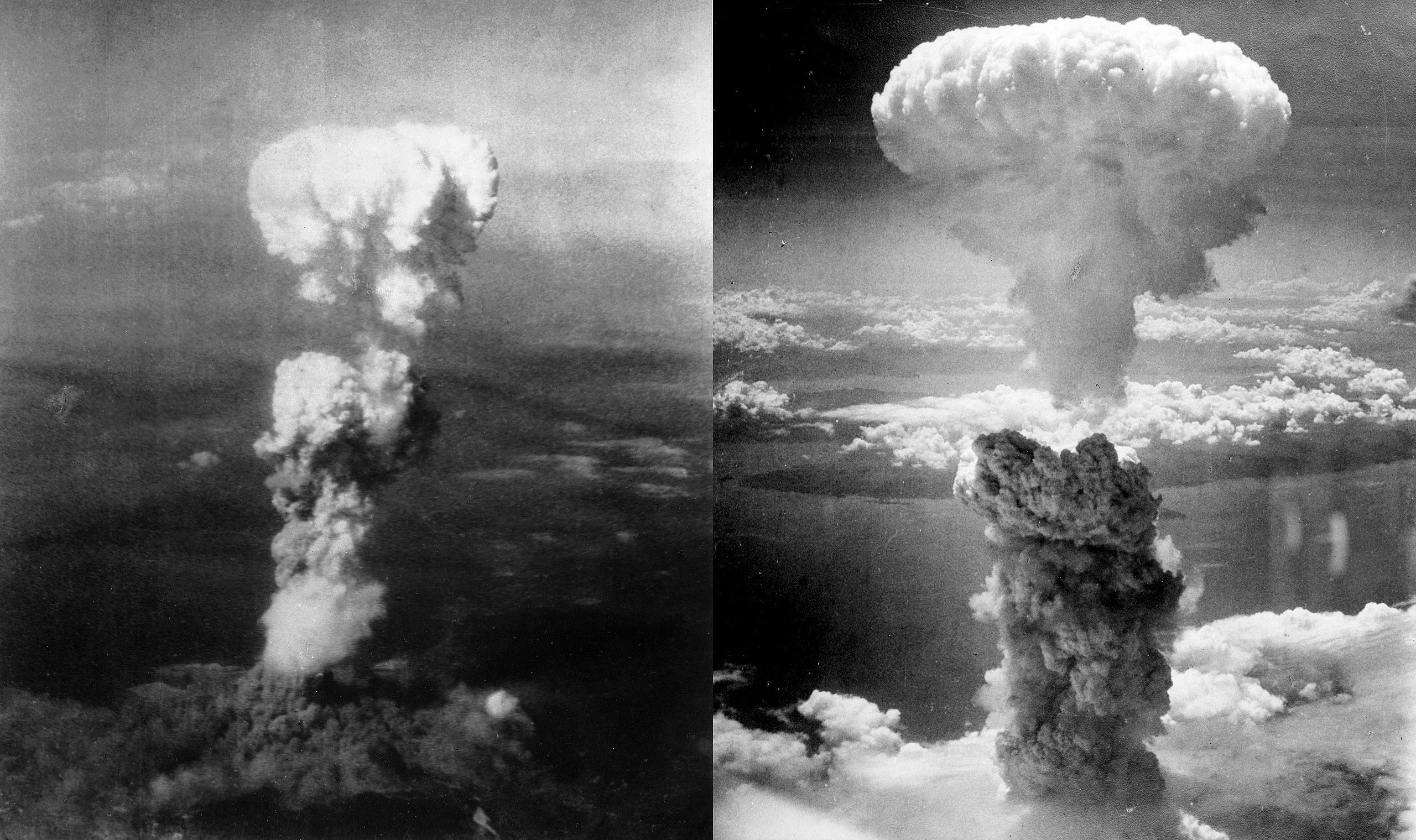

On July 16th 1945, in the middle of the New Mexican desert, a fireball erupted. The infamous Trinity Test had been conducted. The bomb worked. Around a month later, in the city of Hiroshima, Japan, the first bomb was dropped.

Buildings were instantly turned to rubble and people were vaporised on the spot, leaving only their shadows on the pavement. Those who weren’t immediately killed suffered from radiation sickness for years afterwards. 3 days later, another bomb was dropped, this time on Nagasaki, another nearby city. Anywhere between 150,000 and 246,000 people were killed in the bombings, the majority of which were civilians. The Japanese issued surrender on August 15th, with the surrender taking effect on September 2nd. World War 2 was over, lasting 6 years and 1 day.

After the bombing, Oppenheimer became and advisor to the United States Atomic Energy Commission, where he strongly advocated for international control of nuclear power in order to prevent a nuclear arms race with the Soviets. After the testing of the first Soviet nuclear bomb in 1949, Oppenheimer was suspected of allowing Russian spies into Los Alamos due to his communist ties. Oppenheimer eventually had his security clearance revoked in 1954 and was shunned from the government until 1963, when Lyndon B Johnson awarded him the Enrico Fermi Award.

Many scholars today still wonder if the use of nuclear bombs on Japan was necessary. Some say that Japan would’ve surrendered regardless and that the bombing was merely Truman showing the power of the United States. No matter what you may think of the ethics of the bombing may be, the impact of the bombing was undeniable, with many people fearing nuclear annihilation due to rising tensions between nuclear powers, a fear that began in the 40s and is still very prevalent to this day.