King Charles I was the second king of the House of Stuart and was crowned in 1625. He was the second born son of King James I of England, who was originally James VI of Scotland before Elizabeth I’s death in 1603, who died without a direct heir. Due to his original Scottish title, the British Isles now became united under the house of Stuart.

Due to this series of coincidences leading to him taking the throne, Charles believed that he was chosen by God to rule England, and that no-one else could interfere with his choices, such as the nobles or people. Due to his belief in his God given right, many actions of his began to anger the English people, and especially angered Parliament.

Unlike today, Parliament was not the governing body of the United Kingdom. They did not hold much executive power and could only convene legally when the King wanted them. However, they had gradually been gaining more power, with them being able to more efficiently raise taxes than the King, making it hard for the King to govern without the approval of Parliament.

Upon his ascension to the throne, King Charles, who was a Protestant, married the Catholic Henrietta Maria, the Sister of Louis XIII of France. While initially seen as a diplomatic marriage and good for international relations, the increasingly Catholic actions of Maria angered the largely Protestant country of England. Not only that but the Thirty Years War, a civil war that erupted in the Holy Roman Empire, was ongoing. Many wanted Charles to intervene in aide of their Protestant allies. Both of Charles’ attempts to assist were catastrophic failures, with many people believing that Charles mismanagement was the reason that the attacks failed.

In addition, the increased power of the Bishop of London, William Laud, was becoming a great concern. He was making his own sect of Protestantism called Arminianism, which shared a lot more similarities with Roman Catholicism than Protestantism. The now reformed Protestant country began to fear that, due to these actions, Charles was a Catholic Sympathiser. England was now a powder keg, and all it needed was one thing for it to explode.

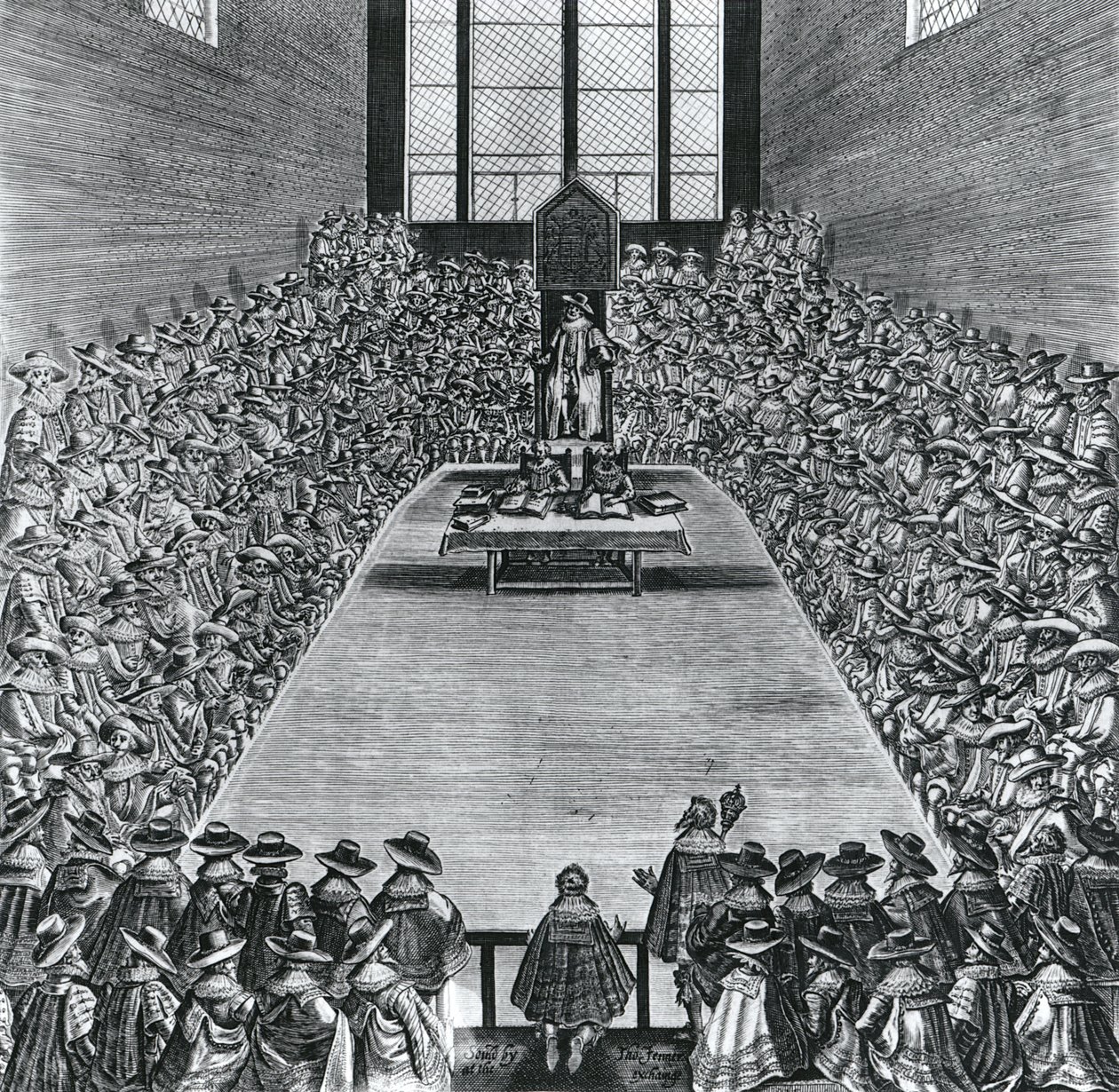

Due to budget restrictions and the rising inflation, Parliament had decided to not raise taxes in 1625, despite the King’s need for money. He instead went about privately collecting the money himself. Many who opposed the money collection were imprisoned without trial, a practice which many Parliamentarians viewed as abusing his power. John Pym, the MP for Tavistock, was a main proponent of the Petition of Right, a bill that limited Charles’ power when it came to collecting money. Parliament supported Pym and a large session was held in which Charles’ money collections were announced in front of the entire room. Charles was outraged and decided to dissolve Parliament in 1629. For the next 11 years, England would be ruled by Charles and Charles alone.

Whilst many from the outside viewed England as a prospering country under the sole rule of Charles, the situation on the inside was a very different story. The need for money was still dire. He began by selling monopolies to individuals or companies. Whilst gaining money for himself, Charles’ actions had angered the people. Merchants could not trade if they were not included in the monopoly, whilst the people were having to pay higher prices for a significantly worse product.

He began introducing old medieval ways of collecting money. One such way were fines for building houses outside the planned city limits of London. While during the middle ages these were intended to deter people away from living in the forests around London, Charles wanted to keep them there in order to keep fining them and making more money. Whilst technically legal, it was very unpopular with the people.

Not only that, but Charles had many Catholic advisors and he felt more comfortable around them. Many believed that Charles was becoming a Catholic, which they feared due to Mary I’s tyrannical Catholic reign, involving the burning of Protestants at the stake, that wasn’t even a century behind them. The people believed that Maria and Laud, who had become the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633, were introducing more and more Papal Influence into the country. Three Puritans, a branch of extreme and conservative Protestantism, named John Bastwick, Henry Burton and William Prynne heavily criticised the actions of Laud. For this crime, they had their ears cut off, a highly controversial act.

One major part of his religious reforms was enforcing the new Book of Common Prayer onto Scotland, in an attempt to make a unified church across Britain. Riots broke out in protest of the enforcement of the new book and Charles quickly sent in the military to deal with the crisis. During the uprising, the English were pushed back and the Scottish Rebels managed to capture a large part of the North East. In order to keep the Scots from pillaging and burning down Northern villages, Charles had to pay them £850 a day

However, he soon ran out of funding. Realising he could not efficiently collect enough money by himself so recalled parliament. The MPs used this opportunity to continue to criticise Charles self proclaimed “Personal Rule”, a period which Parliamentarians called “The 11 Years Tyranny”. After only a few weeks, this Parliament, nicknamed the Short Parliament, was dissolved and Charles continued to wage war against the Scots without Parliament’s support. Due to even more military losses, Charles was yet again forced to recall Parliament in November of 1640

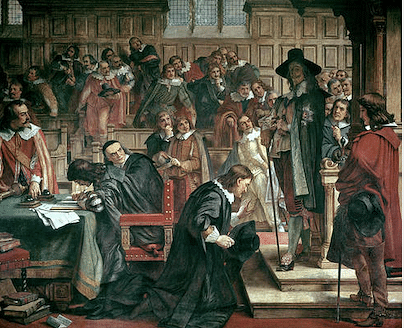

Many acts were passed through Parliament that angered the king. The most important of which was one that prevented the King from dissolving Parliament whenever he wished. Infuriated, Charles gathered 400 soldiers and marched on Parliament, in an attempt to arrest 5 of the politicians who had been pushing these bills. However, they knew of Charles’ plans and went into hiding.

This failed arrest did nothing but turn more people against Charles. Fearing for his family’s safety, Charles fled up north, gathering an army. In London, Parliamentarians gathered their own armies. The country was divided, with Charles’ Royalists (Cavaliers) in the North and the Parliamentarians (Roundheads) in the South. The English Civil War had begun