By Februrary, 1943, the Wehrmacht had just suffered a great loss at the Battle of Stalingrad, in which German forces had just suffered 800,000 casualties and the hands of the Red Army. With German Morale low, Dr Joseph Goebbels, Reichminister of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment, took to the stage of the Berlin Sportpalast to deliver a speech that would change the German attitude to the war.

The German nation is fighting for everything it has. We know that the German people are defending their holiest possessions: their families, women and children, the beautiful and untouched countryside, their cities and villages, their two thousand year old culture, everything indeed that makes life worth living. […] Total war is the demand of the hour. […] The danger facing us is enormous. The efforts we take to meet it must be just as enormous. […] I ask you: Do you want total war? […] I ask you: Is your confidence in the Führer greater, more faithful and more unshakable than ever before? Are you absolutely and completely ready to follow him wherever he goes and do all that is necessary to bring the war to a victorious end? […] Now, people rise up and let the storm break loose!

The applause that ruptured from the hall after this was enormous, with chorus’ of Sieg Heil and chants of “Führer command, we follow!” Nazi banners are raised high. Little do they know, the German people just signed their own death sentence.

As winter set in on the Western Front, the war was not looking great for Germany. With almost all of France liberated, the Italians firmly losing and the Soviets at the gates of Warsaw, Hitler needed a miracle in order to win the war. His miracle would come in the same plan he conducted four years prior.

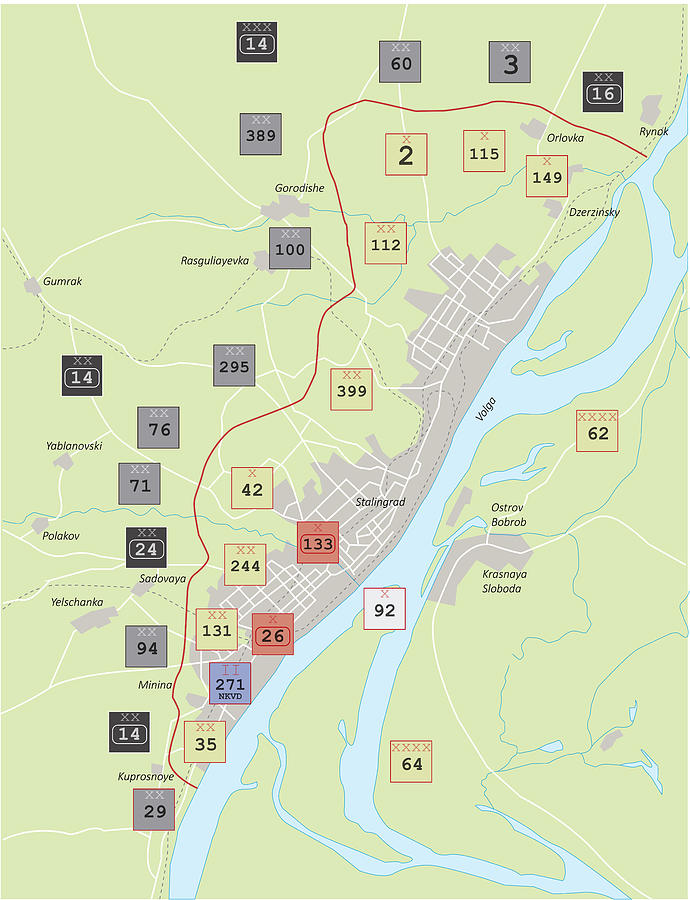

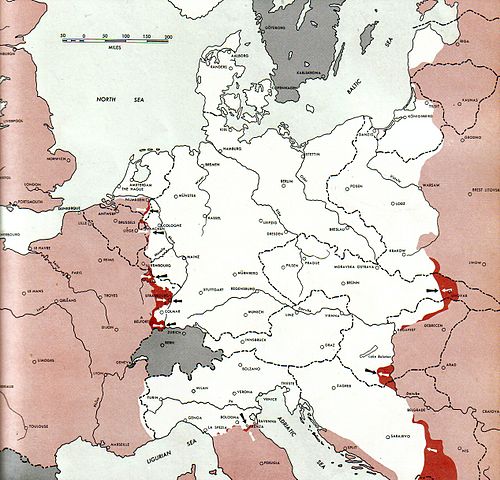

The largely undefended and heavily wooded Ardennes region of Belgium and France began to look promising for Hitler once again. Having initially invading France in 1940 using the same area as a breakthrough point, Hitler planned to push a surprise attack through the area, cutting off most of the Commonwealth forces in the Netherlands, forcing them into another Dunkirk style evacuation. Many questioned the validity of the plan. Whilst Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of the Wehrmacht High Command, was in fully support of the plan, many others, such as Field Marshals Gerd von Rundstedt and Walter Model as well as General Siegfried Westphal, were much more hesitant, fearing that the attack might not even reach the Meuse River. Despite their concerns, they kept silent for fear of being accused of defeatism, which, by this point, had become a crime in Nazi Germany.

Nicknamed Operation Wacht Am Rhine, after a famous Prussian patriotic anthem, every member of high command involved in the offensive was sworn to secrecy at the threat of death, with regimental commanders only being told a day before the attack. In order to not alert American Forces, soldiers used the cover of night in order to advance from town to town, covering up their vehicles when daybreak came. Complete radio silence was enforced during the whole operation. This secrecy had clearly worked, as the Allies were not expecting an attack in any capacity, with Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery of the 21st Army Group confident that the Germans would not counter attack. Whilst the Germans were vastly disadvantaged, in terms of manpower and resources, they weren’t exactly fighting the cream of America’s crop. The defence force in the Ardennes was only seven divisions, most of whom were either new to combat or had been redeployed as an in-work vacation.

Despite the lack of fuel that was desperately needed in an operation through the terrain of the Ardennes, the 6th Panzer Army, commanded by Waffen-SS General Sepp Dietrich, the 5th Panzer Army, lead by General Hasso von Manteuffel, and Erich Brandenberger’s 7th Army, began the assault on December 16th, attacking the North, Centre and South respectively, with the Panzer forces set to capture Antwerp and the 7th protecting the flank from American General George S. Patton’s 3rd Army. Dietrich’s main objective was to capture the key bridges over the Meuse within the first 24 hours of the assault, before an advance onto Antwerp, whilst Manteuffel was to capture Brussels. Before these objectives could be reached, however, St. Vint and Bastogne had to be secured first, as it was crucial for maintaining supplies.

The 1st SS Panzer Division of the 6th Panzer Army was given special care by Hitler, as it contained the most elite troops of the Waffen-SS, including the Peiper Unit, consisting of nearly 5,000 Waffen-SS troops with 800 of their vehicles commanded by SS Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant-Colonel) Joachim Peiper. The full assault was preceded by Operation Grief, in which a brigade commanded by SS Standartenführer (Colonel) Otto Skorzeny adopted American customs, dressed in American uniforms and infiltrated American territory in order to capture bridges, by tampering with road signs, cutting telephone wires and minor acts of sabotage. American forces became so paranoid of encountering one of Skorzeny’s men that they distrusted everyone in an American Uniform, even holding General Omar Bradley, commander of Twelfth Army Group, captive for a short period.

Whilst Dietrich’s Army began with an artillery barrage of American positions, Manteuffel’s fighting force did not go in guns blazing, instead opting for the element of surprise. Despite this disobeying Hitler’s orders of the artillery barrage, the tactic worked well across the board, with many American forces retreating out of fear, with one officer recounting his men wetting themselves and vomiting. The heavy snow also meant that the Allies could not use their superior air power on the battlefield.

Despite the vast and quick progress, this was not consistent across the whole German front. Lieutenant Lyle Bouck of the American 99th Division, for instance, valiantly fended off German forces for the whole day with only 18 men, killing or wounding 400 Germans whilst losing only one man. This vexed Peiper so much that he ordered his unit to advance hard on the enemy position, including into a minefield, losing 5 tanks in the process. Meanwhile, the 326th Volks Grenadier Division advanced north, attempting to cut off American reinforcements but were sabotaged by their own artificial moonlight made out of bouncing spotlights off clouds, which silhouetted them in the horizon, where they were picked off like sitting ducks. In addition, the weather also meant decreased visibility and movement ofr their vehicles, slowing the advance significantly.

Despite these setbacks, German High command was satisfied with initial progress on the first day. However, due to the slower advance, Eisenhower was given ample time to move reinforcements to the front, including the famous 101st Airborne Division, to defend the town of Bastogne and block the German Advance. Meanwhile, Peiper’s unit ignored the orders of Hitler due to muddy paths, instead capturing different towns, where they would massacre POWs and civilians during the Maldemy Massacre, wherein 84 civilians and POWS were executed.

As casualties mounted on the front, especially in the besieged town of Bastogne, an emergency meeting was called between Patton, Bradley and Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, who ordered that the 7th Army cover for Patton’s position in the south, whilst his 3rd Army moved north to relieve the 101st Airborne and the 28th Infantry Divisions. Even with continuous artillery fire that prevented the Germans from capturing the city, they managed to encircle the 101st and 28th. The Germans were incredibly confident with a potential victory at Bastogne. Despite not having the strength to destroy the defenders of Bastogne, General Heinrich Freiherr von Lüttwitz of the XLVII Panzer Corps sent a demand for surrender to General Anthony McAuliffe, commander of the Bastogne Garrison and Artillery Commander of the 101st, simply responded with the following.

To the German Commander.

NUTS!

The American Commander.

McAuliffe’s response to Lüttwitz’s demand for surrender

Eventually, the snow began to ease up, allowing for Allied air superiority to make a comeback, conducting a massive supply drop onto the besieged troops at Bastogne, whilst fighter bombers proved extremely effective at breaking up German attacks. Despite this, Patton strill struggled to breach the German encirclement, repeatedly vexed by blown bridges, activities done by American engineers in order to slow the Germans earlier in the battle.

German Chief of the General Staff, Heinz Guderian, urged Hitler to withdraw forces from the Ardennes, citing it as a massive failure and to put more supplies into the East. However, German forces had just captured Celles, the furthest west of the advance, which buoyed Hitler’s spirits, and so the struggle went on.

Despite this achievement, supplies were running low, to the point where not even a full withdrawal was feasible. When American forces recaptured Celles, they found starved and exhausted Panzer troops greeting them. Runstedt now had to inform Hitler that the plan was a mass failure, to which Hitler, in a fit of rage, dismissed him. Eventually, Patton relieved Bastogne in the most Patton way possible, via a reckless charge from the north, accompanied by storms of napalm.

In a moment of delirium, Hitler commanded that no effort be spared in crushing Bastogne, having forgotten the objective of Antwerp entirely. In attack after attack, more and more lives were lost to Allied Air Superiority and artillery fire, with the Germans eventually giving up and retreating by January 11th of 1945. The Battle of the Bulge, which it was later dubbed, served as the last major offensive operation by the Third Reich, which only delayed the inevitable and now it was a desperate retreat back to Berlin.

Casualties

- United States – 81,000

- The Greater German Reich – 63,000-100,000+

- United Kingdom – 1,408